Looking at the news, it might seem like Iran’s main connection with Israel is its recent missile attacks and ongoing involvement in the Israel-Hamas war. But that’s far from the truth.

Not only do Israel and Iran share a fascinating history, but Israel has also been home to a vibrant Iranian Jewish community for the past 140 years.

“Iranian Jews are exceptional because they are the longest-standing Jewish community in exile, dating back 2,600 to 2,700 years,” explains Professor David Menashri, professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University and founding director of the university’s Alliance Center for Iranian Studies.

“There have always been Jews in Iran since then,” said Menashri, who was born in 1944 and emigrated from Tehran as a child.

Professor David Menashri. Photo courtesy of the Maccabim Foundation.

Professor David Menashri. Photo courtesy of the Maccabim Foundation.

“Obviously, their circumstances have been good and bad at times, but over the years there has always been a flow of Iranian Jews coming here, usually for the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.”

Three waves

Iranian immigration to Israel occurred in three main waves.

The first immigrants began in 1881 and were religiously motivated: they arrived in the Land of Israel after a long and difficult journey and came to such ancient Jewish cities as Jerusalem, Tiberias, Safed and Hebron.

The penniless newcomers were not warmly welcomed by local Jews because they were neither Ashkenazi European nor Sephardic Middle Eastern, and they did not speak Arabic, Yiddish, or Ladino. Many of the newcomers became peddlers and, in some cases, beggars.

8 Must-Read Books on the Israel-Iran Conflict

On the night of April 13, Israel faced a massive Iranian drone and missile attack that may have been one of the strangest in the country’s history.

Thankfully, this historic event was thwarted in the most spectacular way, with millions of people awake at night watching the sky and television.

read more

One of the most famous Iranian families to arrive in that wave of immigration was the Banais, many of whose members have influenced Israeli music and theater ever since.

As their name suggests, the Banai family were building contractors in Iran and continued to do so after arriving in Jerusalem, building the first residential area outside the Old City walls.

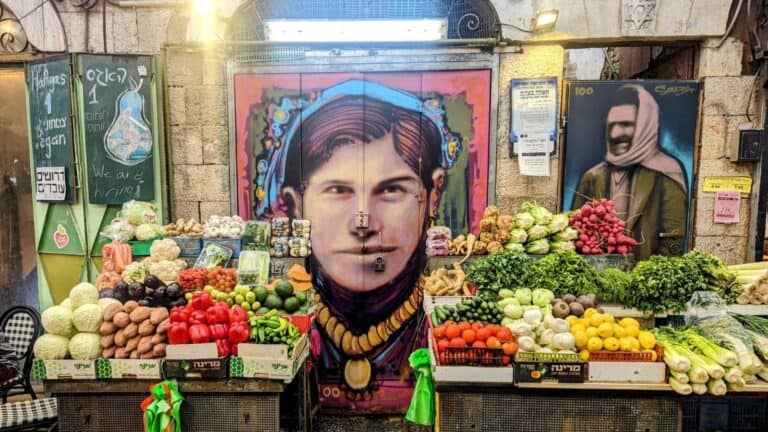

This market stall on Agas (Pear) Street in Mahane Yehuda was renovated for its 100th anniversary and features portraits of the original owners, Bachora and Meir Banai. Photo by Solomon Souza

This market stall on Agas (Pear) Street in Mahane Yehuda was renovated for its 100th anniversary and features portraits of the original owners, Bachora and Meir Banai. Photo by Solomon Souza

The next wave of immigration began with the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Over the next three decades, approximately 60,000 Iranian Jews arrived, mainly at the beginning of that period.

Unlike Jews from Egypt and Iraq, they were not expelled from their home country and traveled back and forth frequently, maintaining ties with relatives and friends in Iran.

A mother and two children arrive at Lod Airport in Israel from Iran in 1951. Photo: Teddy Browner/Government Press Office

A mother and two children arrive at Lod Airport in Israel from Iran in 1951. Photo: Teddy Browner/Government Press Office

They also migrated in nuclear families, and settled primarily in larger cities across Israel, rather than large families settled together in a few pre-determined locations by the state, as was the case in North African Jewish communities, which, Menashri points out, made it easier for them to integrate into Israeli society.

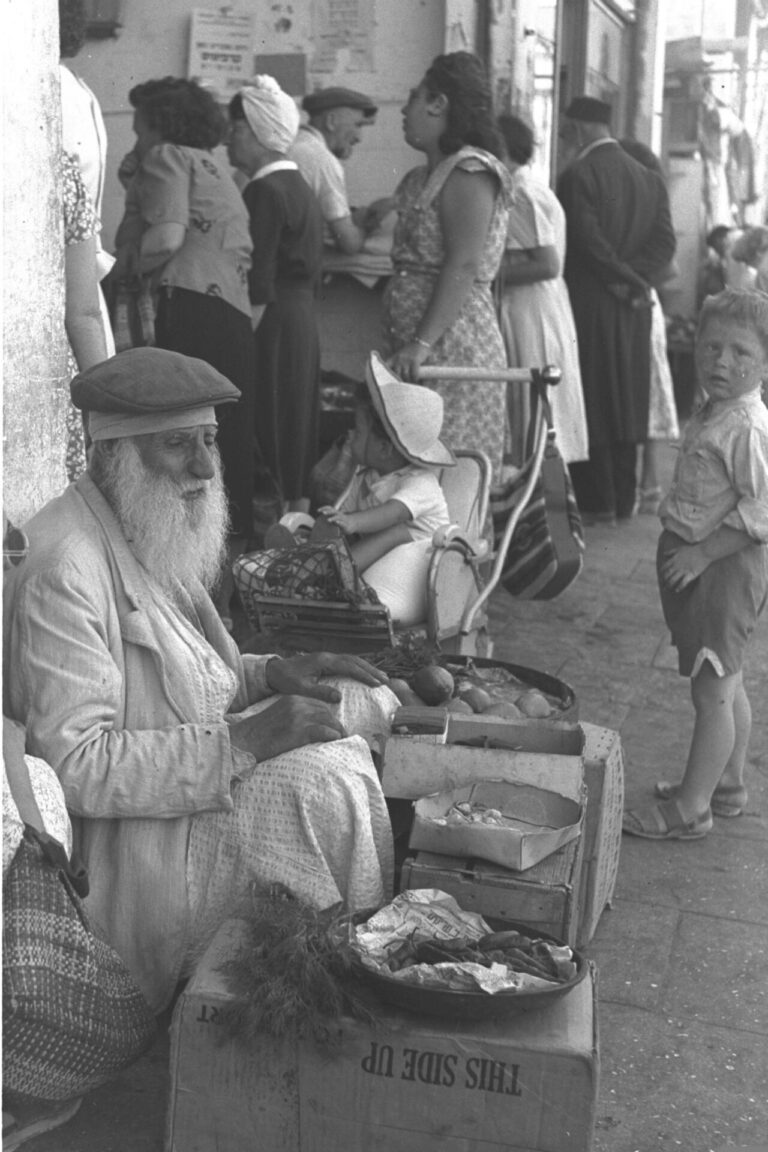

An elderly Iranian Jew sells vegetables for soup at the Carmel Market in Tel Aviv, 1949. Photo: David Eldan/Government Press Office

An elderly Iranian Jew sells vegetables for soup at the Carmel Market in Tel Aviv, 1949. Photo: David Eldan/Government Press Office

There was no large influx of Iranian Jews to Israel in the 1960s and 1970s because the Iranian Jewish community was doing well under the Shah’s rule, but things changed after the Islamic Revolution and a third wave of immigration began in 1979.

revolution

“When the revolution broke out, what was previously considered good became seen as evil. Israel, which had been Iran’s friend, became the revolution’s sworn enemy,” Menashri explains.

On the eve of the revolution, there were about 90,000 Jews in Iran; today there are 10,000.

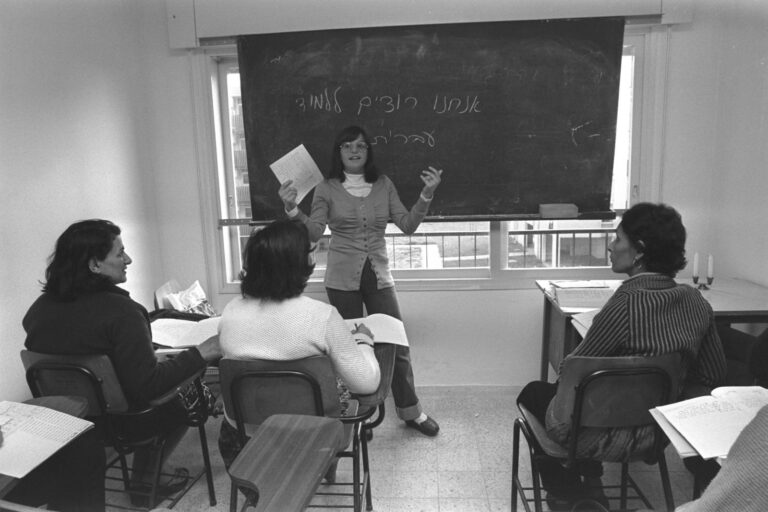

New Iranian immigrants attend a Hebrew language class in 1979. Photo: Moshe Milner/Government Press Office

New Iranian immigrants attend a Hebrew language class in 1979. Photo: Moshe Milner/Government Press Office

“In Iran, people were executed for being Jewish, Jews migrated to Israel through the Kurdish mountains, others through Pakistan, some crossed the snowy mountains into Turkey and then made it to Israel. These are all difficult and amazing stories,” he said.

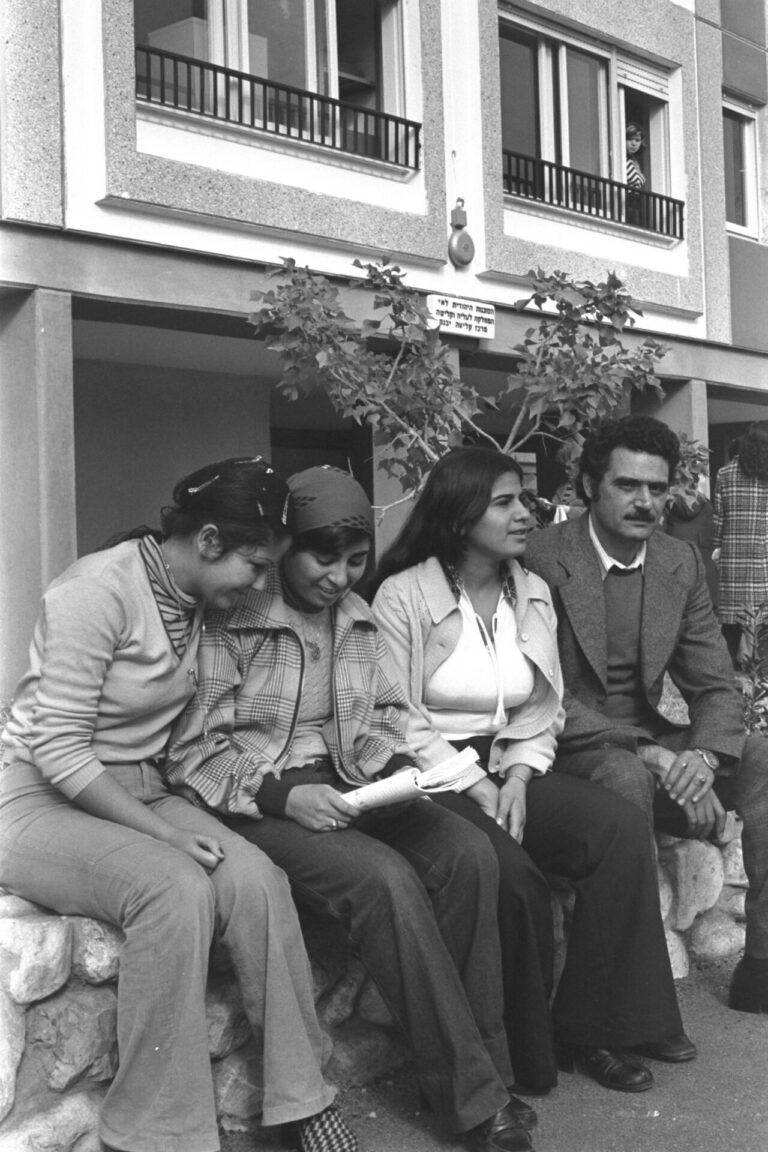

Young newly arrived migrants from Iran sit outside a detention centre in the city of Yavne in 1979. Photo: Moshe Milner/Government Press Office

Young newly arrived migrants from Iran sit outside a detention centre in the city of Yavne in 1979. Photo: Moshe Milner/Government Press Office

Menashri noted that only a third of the Jews who left Iran after 1948 made it to Israel, with the majority going to the United States, Britain and other European countries.

A big difference between the Iranian Jewish community abroad and in Israel is language: Very few second- or third-generation Iranian Jews in Israel speak Farsi, he said, whereas in other parts of the world they do.

“They can’t read or write Persian, but they can speak it,” he explains. “For Persian-Jewish exiles in the diaspora, Persian protects their Persian identity and their Jewish identity. Speaking Persian helps you maintain your Persian identity and not assimilate.”

Liora Handelman Bavour, a senior fellow at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies, explains why this happened.

Dr. Liora Handelman-Bavre. Photo credit: Moshe Bedarshi

Dr. Liora Handelman-Bavre. Photo credit: Moshe Bedarshi

“The first wave of immigrants felt the need to integrate into Israeli society and adopt the local culture while erasing or suppressing their own original culture. As a result, some families from this first wave of immigrants have children and grandchildren who cannot speak or read or write Persian and have lost most of their connection to their culture.

“We can see that in the later waves, the culture was better preserved. This is reflected in the knowledge of the (Persian) language, the cuisine and the proverbs used.”

Persian is cool now

Handelman Bauer added that Israel became a more multicultural society in the 1990s, and the desire for authenticity led people to identify with family traditions.

And after decades of negative perceptions of Persian Jews in Israel due to issues of stereotyping of Persian Jews in Israeli films, Persian Jews are now being viewed more positively, she noted, as evidenced by the popularity of the hit TV show “Tehran.”

“The TV show ‘Tehran’ is broadcast in primetime and is largely in Persian. The acceptance of Persian on primetime television is a clear indication of this change; people were comfortable hearing Persian on TV,” she noted.

“Now we receive consultations from parents who want their children to study Persian in high school or higher education institutions. Adults are also expressing interest in learning more about Iran’s history and culture.”

She sees this as a positive change.

“In the past, it was embarrassing to say you were Persian, but now it’s completely different.”

Besides the Banais, other Iranian-Israelis well known in Israeli culture include Rita Jahan Farrows and her niece, actress and singer Liraz Charkhi, who joined Tehran and has released two albums in Persian, garnering an Iranian and international following.

Israel’s arch enemy

But what most Israelis are interested in understanding about Iran is why it is Israel’s sworn enemy.

These days, whenever you open a newspaper, you find an article about Iran’s evil intentions towards Israel.

“The conflict between Israel and Iran over the last 20 years or so has brought the Iranian community in Israel into the spotlight and made them more confronted than they were before. People who know about Iran are now being asked for clarification, what Iranians think, what their motivations are,” Handelman Bauer said.

Menashri recently published a comprehensive book in Hebrew on the history of the Iranian community in Israel, detailing their origins, immigration and life in Israel, with fellow contributor Handelman Bavour.

“We are living in a time when those who remember Iran and who emigrated from Iran in previous waves of migration are dying out,” Menashri concludes.

“What bothers and comforts me is that there are no Jews left in Iran. There is no future for Iranian Jews. Those who left Iran would have been better off leaving sooner,” he added.

“That’s why it was important to publish this book. It not only tells the historical and academic story of immigration and immersion in Israel, but it also humanizes this story. It relates to the people, women and men, who were involved in this story, and through them, it can tell the story of the journey and immersion in Israel.”